- Home

- Gary Mulgrew

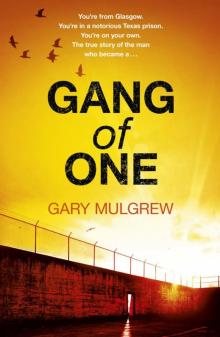

Gang of One: One Man's Incredible Battle to Find His Missing Page 4

Gang of One: One Man's Incredible Battle to Find His Missing Read online

Page 4

It didn’t help that to Calum, my family and close friends I had to appear relaxed, almost unconcerned. I had learned the hard way that showing my true fears to them was very damaging.

When I had originally been indicted – could it really have been six long years ago? – I had spent about a month openly ‘catastrophising’ to anyone who would listen. How selfish I was. Eventually, my Uncle Martin – having listened to me lament pathetically for a number of days – took me aside and spoke to me. He was a man’s man, the quintessential working-class Scot, and the nearest thing I’d ever had to a real father.

‘You need to get a fucking grip of yourself and stop acting like a fanny,’ he’d growled at me. ‘Can ye noo see the impact of what yur doin’ on the people around you?’

‘I . . . I haven’t . . . I didn’t . . .’ I stammered back, realising in that instant that he was, of course, right.

‘Aye, ye “hav’nae this”, ye “did’nae that”,’ he said, mimicking me with real disdain, shocking me all the more because I knew how much he loved me.

‘This is hard on all of us, and we all need you tae be strong. We all need ye . . . tae . . .’ he hesitated, suddenly becoming very emotional. ‘Well just get a fuckin’ grip will ya?’ With that he let me go and stormed away. I stood there rooted to the spot. I’d never thought Uncle Martin needed me as well – I’d never thought I had to be strong for him too – but now I understood. I understood how I had to be, for his sake, for my sake, for everyone’s sake.

Reid was still waiting for an answer. ‘I try not to think about it much,’ I bluffed. ‘Anyhow, if you’ve lived in Glasgow through the seventies, everything else is a cakewalk.’

‘It’s good you can joke about it,’ Reid replied, solemnly. ‘Because I would be terrified. I wouldn’t be able to sleep thinking about all those gangs and nutcases there and how you’ll stand out like a sore thumb and you’ll . . .’

‘Reid.’ He stopped. ‘Shouldn’t we be going or something?’

We took a taxi to Bush International, and quickly boarded the 8.35 a.m. Continental flight to Midland/Odessa. The plane was pretty empty and Reid kindly offered me the window seat. No one else looked like they were casually flying up to go to prison, and it felt distinctly odd to be doing this of my own free will. I sat with my head pressed against the window staring down at the runway as we took off. Each passing minute was putting me more on edge. Was Reid right? Had I prepared enough? Could I handle this? Would I get stabbed to death the first time I went to the showers – or maybe they’d wait till I fell asleep in my bed? I’d been angry with Reid for voicing his concerns, but only because they were my own.

Many years before, when I had been fighting the extradition and fearing the worst, I had signed myself up on a positive-thinking course called MindStore, run by a Glaswegian called Jack Black. Being run by a fellow Glaswegian gave the course an edge of realism I had failed to find in management or lifestyle courses run by Americans – Jack Black was down to earth, relating his coping techniques to everyday events in a ‘normal’ person’s life. He didn’t cover the topic ‘What To Do If You’re Being Extradited’, but I took a lot from the course and the books he recommended. I’d used some of his ideas when preparing for prison in Houston. My mum had always taught me when you had a difficult decision, or something was daunting, to take a blank sheet of paper and write it all down. Jack Black had taken this to a whole new level, more a form of mind-mapping, not simple lines of positives and negative columns. He’d use shapes and colours, arrows, highlighters – anything that would help you get a ‘feel’ for the problem. And this was one problem I needed to get a feel for. So one day, a few months before that final journey to jail, I got up and chose to deal with the problem in front of me. The problem was: I was going to prison.

I sat in silence at my kitchen table in Houston with just blank sheets of paper and some coloured felt-tip pens. In the centre of the page, I wrote one word: PRISON. Using a red pen, I then wrote out all the words that held my deepest, darkest fears. I ‘brainstormed’ – or more accurately ‘brain-dumped’. Not asking why or how I came up with these words, I just wrote them out in bold, clear, red letters as they came to me. First of all I wrote ‘rape’, my number one fear. I really didn’t want to be raped. Then number two, ‘buggery’; pretty much the same as number one, but a bit more specific. ‘Shagged’. Very similar to number one and with a striking resemblance to number two, but these were just the words coming out and I went with the flow. Shagged, raped and buggered – decent scores in a Scrabble game, but not so great otherwise. And then number four: ‘darkness’. Would I be in darkness at night in the cells? How would I even begin to cope with that, especially if it came hard on the heels of an afternoon spent being raped, shagged and buggered? Then I wrote ‘buggery’ again (I’m not sure why), then ‘violence’, ‘darkness’, ‘murder’, ‘extortion’, ‘blackmail’, ‘bitch’, ‘knives’, ‘death’, ‘gangs’, ‘gang rape’. The words just poured out, often repeated. I didn’t know why, but each one more frightening than the last. I stopped and looked silently at the bright red pen against the pristine white paper. I was breathing heavily. A pretty depressing list, and yet it had helped to write it down. It was all there now, previously unspoken, but at least now acknowledged. And confirmation, if I needed it, that I was justified in being terrified.

Next, in blue, I wrote out the other problems I faced – not so life-threatening, but problems nevertheless. First came boredom, then loneliness, fear, discomfort, then loss of choice. I drew branches out from these in green and got more specific. Little or no contact with Calum, or with Julie, or with the rest of my family. How would I survive that? Further away than ever from Cara. Would I ever find her? I’d made so little progress on her case. Perhaps the trail would go completely cold? No visits. Infrequent and short phone calls, if any. Long periods locked alone in a cell. No exercise. Poor diet. Limited amount of food. Bunk beds. No pillows. Thin mattress, thin blanket. No tea or coffee (a big one for me). No TV. No savouries, no chocolate! Shared toilets. Hard toilet roll. No body products. Bic razors? (Oh, how I hated those.) I put a question mark because I didn’t know how people shaved in prison. Would they seriously give some of these guys a razor? Cold showers. Prison clothes. Strip searches. Invasive strip searches. ‘Humiliation’, I added, as I thought of my old friend Marshal Dave.

For the positives I chose yellow – a brighter colour and one that I always connected with hope in my mind. Now, the positives. I paused. What were they exactly? Well, I wouldn’t have to cook on my own. That was a good one, yes. Next. Erm . . . There must be some. Ah, yes: reading. So many books that I’ve wanted to read over the years, this could be my one and only chance. I scrolled down and wrote ‘catching up on my reading’ in luminous yellow. Pleased with myself, I sat back looking at the brightly coloured design on my desk. Even just beginning to note some positives was making me feel better already. I sat back and looked again at what I’d written and, as I often did on my own in that apartment, spoke out loud.

‘So, on the downside we’ve got rape, buggery, murder, my pathological fear of the dark, and generally living in complete fear, poverty and deprivation for years, while the upside is . . . I don’t have to cook for myself and I can catch up on some reading. Mmmmm . . .’

My hopeful mood evaporated. There must be more positives, I told myself. I would have time to think. Loads of time to think. Put it down. I could learn stuff, new stuff. Another language, perhaps. I needed to work on my Spanish, since so many of the US prisons were full of Latinos – particularly in Texas. I wrote ‘improve my Spanish’ down. I’d probably lose some weight. That had to be seen as a positive, surely. Then, of course, it would be interesting; terrifying, worrying, scary also, but even so, still interesting. And that was it. I had run out of positives. My map looked more balanced but, in truth, the reds dominated. Draw it out any way you wanted, but the overall conclusion would be the same. This was going to be hellish. Going to prison is s

hit.

I moved uncomfortably in my aeroplane seat. Reid seemed to be dozing. We were cruising now at 33,000 feet heading north-west towards Big Spring. I couldn’t see much out of the window, so I closed my eyes and tried to think more about how I had prepared for this day, hoping it would give me some semblance of confidence. I had done everything I possibly could, right?

When I’d finished that brainstorming session in my soulless apartment, my next step had been to try to neutralise the negatives as much as possible. Looking at them again, they broke down into two distinct categories. After searching for something appropriate I labelled the first group BAD – things like poor diet, boredom, bad beds, no pillow, cold showers, shared toilets, no tea or coffee; basically a loss of all the little luxuries of life. The second heading covered murder, rape, violence, death, etc., so after some thought I named that group FUCKING CATASTROPHIC, as that seemed quite apt.

Strangely the BAD list didn’t seem that bad when I kept glancing at the FUCKING CATASTROPHIC list, but I made the decision to deal with the BAD list first. I understood that prison attacks your self-esteem by taking away not just your freedom but your freedom to choose. It deprives you of things and that, in turn, leads to a further loss of esteem. So many times the problems and violence I’d read about were triggered by the simplest things: another cold shower, a blunt and uncomfortable shave or a spilt cup of coffee. So I made a decision. I wouldn’t allow the prison to deprive me of these things – I would choose to get rid of them myself. Without dwelling on it any longer, I stood up from the table and the piece of paper, walked into my bedroom and stripped the quilt off, leaving one thin blanket, and then after hesitating for a second, I took off all the pillows. In the bathroom, I stripped out all the toiletries except for one bar of soap, some toothpaste and a toothbrush. I would buy and use only Bic razors from here on in. I would only have cold showers, no hot water and no baths. In the kitchen, with some reluctance, I binned the tea and coffee. That was going to be a challenge for me, but I realised that these small steps would all help me to feel mentally stronger and better prepared. Either that or I was turning into a lunatic. I wasn’t entirely sure.

Next, I disconnected the TV and cancelled my satellite subscription. I packed away the stereo, but kept a small radio as I figured I would still have access to one inside. I looked at my small wine stack, but at that point my will faltered. The wine was helping me. I was a bit worried about how much I was drinking – about a bottle a night, sometimes two – but I understood why. I was alone in Houston. I didn’t have my family, I didn’t have my friends. I was going to prison. I didn’t feel my drinking was out of control or a physical problem. Julius Caesar, no less, had once said, ‘Give me a bowl of wine. In this I bury all unkindness.’ If it was good enough for a man in a short skirt, then it was good enough for me. So the wine stayed and I comforted myself by throwing out all the chocolates, biscuits and other treats that I doubted would be available in prison. These were my attempts to wrest control back from the prison – to make it my choice to forego these luxuries; to avoid going ‘cold turkey’ on life’s little pleasures at the same time as I faced those dangerous first few weeks in prison. Much of these techniques were management practices I’d used when dealing with big issues in business. I’d no idea whether they’d translate to the setting of a prison, but I had little choice but to try.

Having stripped away the simple things, that still left the major issues: the fears I deemed ‘FUCKING CATASTROPHIC’. I had to grapple with them. At once it occurred to me that I didn’t know if these things actually still did happen in prison. People obviously did get raped, but was this an unusual or a common event and surely there were steps you could take to minimise the danger? Murder and violence came under the same heading. Truth is, I didn’t know enough about it – I needed to research it and analyse the reality of prison life. I had studiously avoided reading things on prisons in the US especially after Marshal Dave – it was too scary – but I realised this had to change; I would have to start reading everything I could and that extended to the topics I feared the most. I knew that prison gangs were prevalent in a lot of the US jails – not so much on the East or West Coasts, where I had originally hoped to be placed alongside Giles and David, but certainly in Texas. I decided I’d better learn about them fast: how they worked, and what the ‘rules’ were. Most of this info would be available on the Internet, I reasoned, but I had to have the courage to read it.

With regard to the violence I was sure I would face, I decided I needed to do a physical stocktake of myself. As far as being threatened, I had one advantage: I was big. Just over 6ft 2, and at that point around 190lb. In the UK, being from Glasgow was always an advantage – people always assumed you were hard, not realising in my case that I was anything but. My bashed-up nose (caused by an operation to rectify a deviated septum, not any vicious man-fighting) gave me the look of a boxer at times. I focused on the large number of scars on my arms (caused by operations to remove various cysts over the years) and thought that at least gave me a further ‘tough man’ boost. Then I had my thistle tattoo on my right arm over my bicep, and tattoos were meant to be tough, right? A few ticks in the right boxes.

I had actually worked as a bouncer in a Glasgow nightclub for four years while at university. This might be impressive stuff for any prison CV, although the reality was that my natural fear of being punched, nutted or knifed by the assorted head cases who frequented the club had meant I sailed through four years without getting involved in one fight (although I did once wrestle an aggressive girl to the ground to stop her punching her boyfriend on the head). While I hadn’t actually exchanged blows with anyone, that and my time growing up in the tenements of Dormanside Road in Pollok – a housing estate that was Glasgow’s seventies successor to gangland Govan – had given me an uncanny antenna for spotting potential violence or disturbed body language, and techniques for avoiding it. Avoidance was always the safest route. I felt this talent would be getting significant usage in Big Spring, and I looked at that experience now as being a positive.

The negatives I saw, as I stripped down naked in front of my bathroom mirror, were numerous. Number one: I was flabby. I was forty-six and the middle-age spread, while not being too pronounced, was definitely there. I had been a keen sportsman most of my life, but mainly football and golf. My upper body lacked definition, my arms lacked strength. I didn’t look very intimidating. I realised, of course, that I wasn’t entering a strong man competition, but this was all about my own self-confidence. As a bouncer, I had learned that in nearly all situations a calm, confident persona would defuse even the most psychotic Glaswegian. But you had to be confident in yourself and it helped if you looked tough. I looked more critically at myself in the mirror. The curly hair would have to go. I had a heavy growth, almost a beard and quite dark, so I’d keep that.

During all of this appraisal, without admitting it, my eye kept being drawn to my rear end, my rump. I hadn’t really thought of it before, but I had a huge arse. It was much bigger than I could ever remember it and, horror of horrors, it started to wobble when I walked. When did this happen? I meandered up and down a couple of times naked in front of the full-length mirrors. It looked enormous. And it was out of proportion to the rest of me. It was a notably large arse. Not only that, but with the rest of me having become quite brown in the Houston sun, it was an especially white arse. This sent me into a tailspin of panic. My large, white arse would be like a beacon to every bum-rapist throughout the prison – I could become a prized possession. I had read once that they liked straight guys more and they saw it as taking your virginity – or was I thinking of The Shawshank Redemption again?

What would happen in the showers, the dreaded showers? My carefully written out diagram was becoming a blur as I descended into panic. I remembered all the jokes about not bending down to pick up the soap. I looked at the bar of soap by the sink tap. Without thinking much more about it, I reached across to it and threw it down on

the floor. ‘Pick it up, Mulgrew,’ I thought to myself. ‘Pick it up, wobble bottom.’ Slowly I leaned forward to collect the bar, while watching myself carefully in the mirror. ‘Oh, my God,’ I blurted out. Bending over seemed to make my arse look larger. My arse had expanded. I looked like a big light bulb, a neon sign saying, ‘Over here boys!’ This was a disaster. I replaced the soap and tried again, this time clenching my buttocks as tight as I could (harder to do than you would think). That gave my buttocks a shape and form I really didn’t want them to have. Attempt three involved crouching to pick it up, which momentarily I thought was a winner until I realised my head was now at dick level and I was picking up the soap like a girl, all dainty and delicate. That sort of act could just encourage the crowd. Standing up, I kicked the soap across the room. ‘Fuck it,’ I thought. ‘If the soap drops, I’ll stay dirty.’

At least these reminiscences of me playing the fool made me smile a little as I shifted in my aeroplane seat. The flight to Big Spring would only take an hour and a half and we had already been in the air for thirty minutes. I felt the need for a drink, an alcoholic one even this early in the day, but I guessed they would be testing me when I got there and didn’t want to have anything in my system. I’d need all my wits about me.

I looked out of the window and saw the brown scrubland below; just an empty wasteland. I could populate that emptiness with fear, or stick to my careful, determined preparation. I forced my thoughts back to all the work I’d done in the months before.

The fitter and stronger I felt, the less likely it would be that I would be attacked; that was my core logic. So first of all, I needed to go into training. It was not just a question of stepping up my usual running and weights routine, but also of learning self-defence and focused, clear attack techniques. I hadn’t suddenly gained an upsurge of courage, but the soap sketch had been about confronting one of my deepest fears and I wanted to be in a position to defend myself if need be. My thinking was: if I did get into an awkward situation and my fat virginal white ass proved too much of an attraction, then at least I wanted to be able to handle myself. After all, Tim Robbins always gave as good as he got in Shawshank.

Gang of One: One Man's Incredible Battle to Find His Missing

Gang of One: One Man's Incredible Battle to Find His Missing